Jean-Louis Chanéac

Forgotten Futurism

Welcome to our blog series Ghosts of Design— where we deep dive into the forgotten, the overlooked, and the radical minds who reshaped architecture & design but never quite made it into the mainstream.

This is the first in the series, and we’re starting with Jean-Louis Chanéac, a visionary whose ideas of parasitic architecture, modular urbanism, and adaptable cities were decades ahead of their time.Jean-Louis Chanéac never quite fit in. He wasn’t one of the Archigram stars designing inflatable cities in London or a Japanese Metabolist using megastructures for corporate branding. He wasn’t even as well-known as his fellow French visionaries such as Yona Friedman, Claude Parent, or Pascal Haüsermann, though he worked alongside them, speaking the same radical architectural language.

Instead, Chanéac operated on the periphery of the future, a forgotten architect of speculative urbanism. His visions were wild, utopian, and only partially realized suggested a world where architecture didn’t just grow, but mutated. Cities wouldn’t be frozen in steel and concrete but infested with parasite-like modules, transforming over time like living organisms.

This wasn’t architecture as we know it. It was architecture as an urban rebellion, an act of taking over and transforming space. Chanéac imagined a world where your home wasn’t a static box, but something that could be attached, detached, rearranged—like a biological extension of the city itself.

The Age of Parasitic Urbanism

Chanéac’s most provocative idea was parasitic housing. These were modular "cellules parasites" that could latch onto existing buildings like barnacles on a ship’s hull. Imagine an entire city growing sideways, expanding unpredictably as residents added bubble-like extensions to their apartments, DIY capsules clinging to the facades of old buildings, entire streets overtaken by modular living pods.The idea was radical, anarchic. Why tear cities down when you could just grow onto them?

But this wasn’t just some sci-fi daydream, Chanéac built prototypes. He spent the 1970s experimenting with these prefabricated, plug-in living cells, creating models and speculative drawings that still look decades ahead of their time. His modular pod concepts predicted everything from capsule hotels to contemporary micro-housing. And yet, while architects like Kisho Kurokawa went on to build the Nakagin Capsule Tower, and Peter Cook and Archigram got their place in the history books, Chanéac’s name faded into obscurity.

‘Cellules Parasites’, Geneva, Switzerland. 1968. Architect: Jean-Louis Chanéac

‘Cellules Parasites’, Geneva, Switzerland. 1968. Architect: Jean-Louis Chanéac

The House That Wasn’t a House

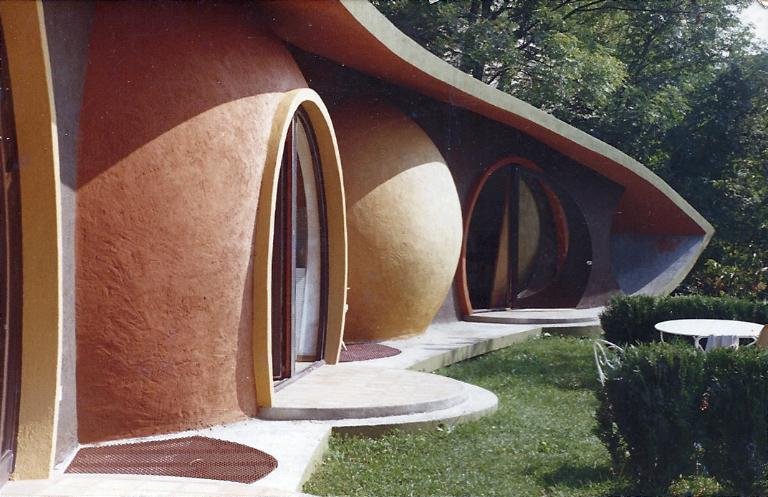

If Chanéac had a manifesto, it was his own home: Villa Chanéac, built between 1974 and 1976 in Aix-les-Bains. From the outside, it looked like a lunar base abandoned by time, or a sprayed-concrete landscape of interconnected domes, bulbous rooms that seemed to spill into one another, a space without clear divisions, without traditional walls or ceilings.

To live in the Villa Chanéac wasn’t to inhabit a house but it was to enter a system, a living experiment. A house that wasn’t a house at all, but a machine for adaptation. You could imagine entire neighborhoods designed this way—honeycombs of interconnected living spaces, a whole city without right angles. But unlike Metabolism, which was often co-opted into corporate-friendly megastructures, Chanéac’s vision was messier, more organic, more subversive. It wasn’t about planned obsolescence—it was about taking control of the built environment, hijacking urban space for personal autonomy.

And this is where his work starts to feel eerily prescient. Today, we talk about DIY urbanism, tactical interventions, guerrilla housing solutions, micro-living, plug-in modules. Chanéac was already there—forty years ago.

Chanéac House, 1976, © Région Rhône-Alpes, Inventaire général du patrimoine culturel

Chanéac House, 1976, © C. Stéfanini

Douvaine: The City That Almost Was

Not all of Chanéac’s ideas remained in the speculative realm. He collaborated on real-world projects, like the Nouveau Centre Urbain de Douvaine, an urban experiment between 1972 and 1977 with Pascal Haüsermann and Claude Costy.

It was meant to be a modular, expandable city, a radical reinvention of urban planning. But like so many of his projects, Douvaine never reached its full potential. The project was killed by shifting political winds, lost funding, and the sheer difficulty of convincing bureaucrats to embrace the urban unknown.

That was the problem with Chanéac’s work: it was too radical, too chaotic for the comfort of city planners. It didn’t fit into the tidy utopias of Le Corbusier’s “machines for living” or the corporate spectacle of starchitect-designed megastructures. It wasn’t scalable, not in the way governments or developers wanted. It was an urban system designed for change, unpredictability, improvisation—things that institutions tend to resist.

The public nursery school of Douvaine, built between 1976 and 1978. (Photo by Nicolas Scoulas)

Architecture as Insurrection

Chanéac didn’t just build. He painted, sculpted, wrote. His work blurred the line between architecture and art, between speculative fiction and real-world possibility. His book "Architecture Interdite" (Forbidden Architecture, 2005) is part-memoir, part-critique—a reminder that many of the most radical architectural ideas never see the light of day, not because they don’t work, but because they threaten the status quo.

He died in 1993, largely unrecognized outside of avant-garde architectural circles. And yet, if you look at today’s urban crises such as rising housing shortages, collapsing affordability, the need for adaptable, resilient cities—Chanéac’s ideas seem eerily relevant.

In an era of climate change, mass migration, and housing precarity, what if we reimagined cities the way he did? What if architecture could grow, mutate, and evolve instead of being demolished and rebuilt from scratch? What if cities weren’t static grids, but adaptable, organic systems? In the end, Jean-Louis Chanéac wasn’t just an architect. He was a prophet of urban parasitism, a designer of cities that never were—but maybe still could be. And if you ever find yourself staring at a city skyline, wondering what it would look like if architecture had evolved differently, if cities had grown not outward but upward and sideways, layer upon layer, like corals and fungi, then maybe, just maybe, Jean-Louis Chanéac is still out there, whispering in concrete.

Furniture store, Châtillon-en-Michaille (Ain). Architect: Jean-Louis Chanéac